When studying for my HND at the Cass London Metropolitan University, students had the opportunity to choose between different optional modules in addition to the compulsory ones. One of those modules was called “Alternative Materials” (which in my opinion should have been called “Alternative Thinking” instead) and was taught by the designer/silversmith Wayne Meeten. His reputation was preceding him and some 2nd year students had warned me: he is really tough and makes students cry… As I was a “mature” student, I took this warning more as a challenge than a danger: me, crying? Never. I defiantly registered for this module.

The first two classes were awful: we had to show images that were inspiring us, and to present our sketchbooks. “Everything is too organised, too tight, too much in control. You have to free yourself. You will be one of my most difficult students”, he told me. Tears were very close but I managed to pull myself together and during the third class we had a little conversation where I told him: “I have spent 15 years working in finance, so Wayne, believe me, I am aware I have to venture into unknown ground. I just need time”… This was the beginning of two very fruitful and challenging years of learning. He was tough and demanding, but fair and passionate. His teaching style didn’t work with everybody, but it definitively did for me and I think it must have worked for my class mates as well because I saw their work transform into wonderful ideas throughout the year. This is why, 3 years later and after completing my MA, I wanted to interview him and understand where his passion came from.

We met in his studio in east London and the first thing that struck me was the cleanness of the space: carpet and rubber mats on the floor, white towels everywhere and perfectly aligned shiny tools. Every hammer, file or stake has been customized to fit Wayne’s hand. “I want my tools to be part of me, they will outlive me. I take care of them, I look after them... And if a piece drops on the floor, it won’t bend or dent because of the rubber mats. It is like a safety net”. Why all those white towels? “Every time I heat the metal up, I put it into acid and then take it out into pristine water, then clean it with soap and white towels. The metal thinks I am really taking care of it and there is a dialogue between us: if it knows I am caring, it will want to become something beautiful”.

Wayne’s studio. Photo Isabelle Busnel

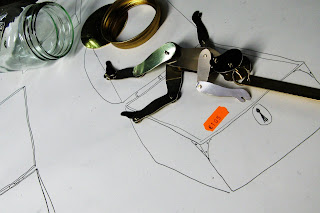

Customized and shiny tools. Photo Isabelle Busnel

Wayne thinks that somehow the metal is alive and has a “God”. This strong belief may arguably have a scientific background: metal is made of molecules, it expands when you heat the metal up, it shrinks and cracks when you harden it. But it mostly stems from a metaphysical and spiritual point of view: metal and humans are made of the same particles and we are all part of a whole, the “Tao”. You must therefore listen to the metal: there is a moment when it starts splitting and at that very moment, the metal is “crying” to ask you to stop. If “you carefully watch it, listen to it, then you can literally hear at the sound of the hammer when the metal is getting hard and you know when it is soft” says Wayne.

To understand this particular bond between the material and the maker, one needs to dig a bit deeper into Wayne’s life. After having being badly beaten up during a street aggression and almost died at the age of 29, Wayne was introduced to Tai Chi during his recovery. The first year was mostly about learning the movements but during a workshop in the countryside, his teacher brought him very near to a huge tree and asked him to look at the scarred, marked and damaged bark. Then both of them walked away 500 yards and his teacher asked him to look again at the tree. “That tree is you,” he told Wayne. After years of therapy and plastic surgery, years of being ashamed of his scars, somebody was comparing him to this tree of life, damaged on the outside but majestic on the inside. This was one of the defining moments of Wayne’s life. He suddenly understood why he had been so inspired by Kandinsky, Egyptian art and 50’s American cars: they were all triangles, angles, and sharp, and that is exactly how he was feeling inside. After discovering Tai Chi, he started to take life drawing classes, to find inspiration in feminine curves, contemporary dance movements, flowing rivers, waterfalls and nature. “The shape I am creating now are really soft and organic”, he says.

Chi Ball. Britannia silver. Courtesy of he artist.

The second defining moment of his life was when he decided to go to Japan to learn a technique called mokume gane (folding, cutting and hammering together different layers of metals to reveal colours and patterns) with Japanese masters. He spent two years at Tokyo Geidai (University of Fine Arts and Music) as a visiting professor but had to learn Japanese first! Those two years were very demanding but acted as a revelation: he met masters that taught him not only technical virtuosity but also Japanese ancestral ways of thinking about metalworking practices. It was as if somebody suddenly expressed loudly what he had been feeling deeply inside for a while. “You are more Japanese than Japanese” was the most extraordinary compliment he ever received from his master.

Professor Norio Tamagawa with Wayne in Mr Tamagawa's workshop in Nigata, Japan. Courtesy of the artist.

Tai chi and those two years in Japan changed his life forever and the Tao philosophy became indissociable from his relation to metalsmithing. To understand it fully, one has to look at him working on metal: bang, bang, kabang, pause, bang, bang, kabang, pause. Like a Tai Chi routine. A pause between each breath. “There is a dialogue, a rhythm, a music, between me and the metal. Then the metal knows that it is me handling it,” says Wayne. Like a dance, every stroke of the hammer has to be exact, precise and in the centre. “If it makes a mark, you dent it and it becomes sharp,” he adds.

Wayne working on his latest piece. Photo Isabelle Busnel

To get to know the metal even more intimately, Wayne is usually buying silver in the form of grains that he will melt into a bloc and then hammer. “When you buy a sheet of metal from a bullion dealer, it has already been worked on by somebody else or a machine and I can’t have a proper dialogue with it, so when I buy a lump of silver, it doesn’t know me yet, which is why I am making my own metal and my own alloys,” he says. Japanese metalworkers are, according to Wayne, the best in the world to make their own alloy because the scarcity of metal on their island have forced them to be experimental and creative in this field. Wayne has learned a lot in Tokyo about understanding the chemical formula of metals: “this enables you to know how far you can push the material before it cries and breaks”, he says.

Inner Golden Facets. Truffle. Mokume Gane and silver. Courtesy of the artist.

(This piece is in he final of the Saul Bell International Design and Crafts award 2011 competition)

Wayne’s profound respect for metal is only one aspect of his Tai Chi and Tao spirituality of which his impressive skills and patience are another face. Wayne has spent 8 years at University and 2 years in Japan learning the fundamentals. “You have to root yourself and grow like a tree. That way, you can become a stepping-stone for the next generation” he says. This is something that our fast paced society has sometimes trouble to cope with. “Young people want to earn quick money, to become traders or rock stars but not to spend 10 years painfully learning a technique,” he says. He is echoed by an interesting quote from Bruce Metcalf (a very thought-provoking jeweller/writer/curator/teacher whose website is full of inspirational texts about craft): “Basic article of faith in the Modernist academy was that careful, controlled work has no aesthetic potential. In Japan and Korea, mastery of technique is understood as evidence of spiritual maturity. To a Buddhist, work spent on attaining skill necessarily contributes to higher awareness. It is regarded as a spiritual discipline to have repeated the same act thousands of times, to have paid careful attention in years of work, and finally to have achieved perfection. Virtuosity is admired not just for its own sake, but because it demonstrates a religious accomplishment”. This quote seems to have been written to describe Wayne’s work… One of his vases can take a month to make - 10 hours a day, six days a week - and that probably explains why he is sometimes so hard with students, as he wishes to teach the value of mastering their techniques whatever the material chosen.

Another thing he was always mentioning in his class: “you are unique, and if you don’t believe in yourself, who will”? He was therefore pushing us to find the gem hidden deep inside ourselves, and didn’t let us go until he thought we had done the best we could which led some students to cry on a regular basis. “Tears are not a bad thing, they are cleansing. Students knew I was opening up areas within them to allow them to grow. It was emotional because I was mirroring what they were thinking and feeling inside but they didn’t know how to express it” he says. Looking at the inner quality rather than at the outside: a philosophy directly inspired from the Tao, the yin and Yang, the positive and the negative and the art of finding balance between them.

Mother and child. Britannia silver. Courtesy of the artist.

This is why, according to Wayne, his vases do not need flowers: the beauty lies inside the forms, the curves and the sensuality of the silver alloy. The “unknown” and the mystery are inside. As he likes to say: “my work goes up inside”.

Inside of the Inner Golden Facets. Courtesy of the artist.

The time spent interviewing Wayne about his life, his work and his Tai Chi practice helped me understand why he was so passionate (and sometimes hard) in his teaching. It also helped me to better understand his work: “being a craftsman, an artist and a designer, I want to tell people in my own way a spiritual message through art about Tai Chi” he said at the end of the interview.

Embrace within. Mokume gane and Britannia silver box. Courtesy of the artist.

The box in the above picture will act as a perfect conclusion for this portrait: it is made of mokume gane and raised Britannia silver, has a sort of yin and yang game playing between the two parts, is sensual and curvaceous, hides the unknown inside and has been virtuously crafted… All of Wayne’s philosophy in a box.